Pierre Boulez Picks 10 Great Works of the 20th Century

Thursday, March 26, 2015

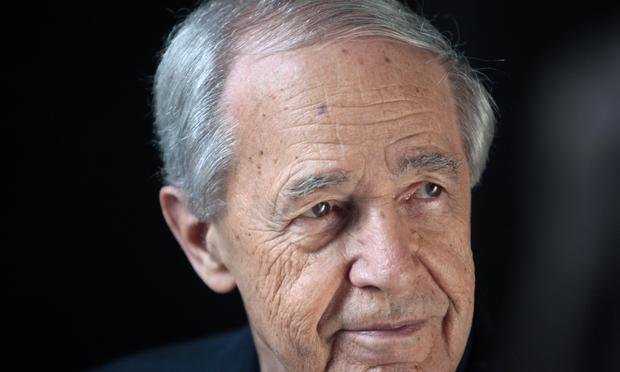

Pierre Boulez turns 90 this year. (Francois Guillot/AFP/Getty Images)

Pierre Boulez turns 90 this year. (Francois Guillot/AFP/Getty Images)Today, March 26, 2015, is the 90th birthday of Pierre Boulez. One of the great firebrands in classical music history, Boulez cut a huge swath through European culture in the decades after World War II. Here in the States, he's probably best known as a conductor – the inventive music director of the New York Philharmonic who did concerts for audiences lying on rugs on the floor in the early 70s, or the man who recorded two of the definitive versions of Stravinsky'sRite of Spring with the Cleveland Orchestra. But in Europe, he's celebrated – or not – for his own compositions, for his provocative writings on music, and for his founding of IRCAM, the famed and influential Paris-based center for research into music and technology.

Brash, opinionated, animated, and often brutally honest, Boulez can seem like an intimidating figure. But he is also funny and charming and very, very smart. I first interviewed him before a concert in Boston by his Ensemble Intercontemporain (an electro-acoustic chamber ensemble based at IRCAM) in 1986. We started late, and finished talking about 10 minutes before he was scheduled to start conducting. I was worried I'd eaten into his prep time and that this would cause a problem, but he picked up his jacket and said, "when I put on the jacket, I am ready. It is instantaneous." Which he then proceeded to prove.

Over the years, Boulez would come on my various other shows (Around New York in the 1990s, Soundcheck in the 00s), but one of the most memorable visits he paid us was early in 2000. Rather than just interview him, again, I asked if he'd make a list of what he considered the ten most important pieces of music in the just-concluded 20th century. I'm not sure what I was thinking – just trying to do something different, I guess, but to my surprise and delight, he agreed. Over the course of a week, we broadcast his Top 10, two pieces each day, with Boulez himself explaining why he chose each piece. Read on to find out what he chose and why.

Boulez: 10 Great Works of the 20th Century

I. Edgard Varèse, Ameriques

I discovered Varèse quite late, for two good reasons. The first was, there were no scores available in France in 1945, '46. Second, there was no recording. Varèse was a kind of myth for French people, a man who disappeared from France in 1915, 1916, far before my time. He came back for just one or two years in 1930 or '31, and disappeared again. He was really a myth.

The first time I came to New York in 1952, I was busy with music. I made the acquaintance at this period with John Cage, and also the acquaintance of Varèse for the first time. We were very good friends. He gave me some scores, and we recorded them a little later. But we began in France, because [his works] were completely unknown there at this time. After that, I discovered the "big" scores. There are two: Arcana, andAmériques.

Amériques is, for me, a work which is quite remarkable. It's a piece where you find the influence of Rite of Spring, it's close to this aesthetic and feeling—more aggressive, more gigantic—but at the same time you have very lyrical passages, which become rarer and rarer in the later works of Varèse. I like this work because it's the first work he wrote when he was in America, and it was the first work he kept. The life of Varèse is full of mystery; after he died in 1965, I met regularly with his widow. We spoke together about him, and of course she could speak more openly about him because he was not alive anymore; and all of the scores he composed before coming to the States were supposedly destroyed in Berlin.

Edgard Varèse, "Ameriques" (excerpt)

II. Alban Berg, Three Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 6

These are the only symphony pieces he wrote for orchestra, because everything else is with voice, or are excerpts from opera or a concerto. Before, you have the Altenberg Lieder which are for voice and orchestra, and later you have the Baudelaire song (Der Wein) which is also for voice and orchestra; then you have a violin concerto, and then you have the excerpts fromWozzeck, and the Lulu symphony. So everything is related to opera, concerto or voice. Only these three orchestral pieces remain, as pieces for orchestra alone. So therefore they are very interesting.

They were written immediately before the First World War, revised later, and in the last piece especially you have an accumulation of things at the end which is absolutely remarkable.

For me they are very dear pieces, very brilliant; you can have an orchestra really shine in such a piece, and show its virtuosity. For me, they are, first, a great masterpiece of the 20th century, certainly, and also they are also very impressive because you feel all this great outpouring of feeling which I find necessary to convince an audience.

Alban Berg, "Three Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 6, III - Marsch"

III. Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring

I discovered Rite of Spring when I was 21. As a matter of fact, not with orchestra first, because it was still a work which was not often performed. Don't forget that I was 19 in 1944, still the Occupation time. So it was performed slightly after the end of the war, in 1945. The first time I discovered it with a real orchestra, it was in '45-'46. But before, being in the class of [Olivier] Messiaen, it was a work Messiaen admired deeply, and we made an analysis of it. We performed it, piano four hands, like in the ballet rehearsals before the First World War. When you are performing it just four hands like that, it gives you a good view of the music, because you are performing it yourself, and you know the difficulties, the rhythmic difficulties. And you can imagine, even in '45 it had still a strong power, can you imagine in 1914 what power it could have had?

When I am playing Rite of Spring—which is easy now with first-class orchestras—you can imagine the difficulty that dear Mr. Monteux [Pierre Monteux] had the first time he was confronted with this work, and especially the musicians! Not everything in the score, but some parts would have been very difficult, because it was the first time musicians had to deal with this irregular pulse. When I think of the Rite of Spring I think always of the conductor of the first performance. I remember one musician, who was supposed to have heard one of the first performances, told me, "You know what I regret? That the bassoon is so easy nowadays." Every bassoon player works on that, and when he comes to a performance he is fully prepared. But at this time, this high register, completely alone, at the very beginning of a work… certainly people were terribly anxious to play it correctly!

Igor Stravinsky, "Rite of Spring (opening)"

IV. Béla Bartók, Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta

That's really a special work—his return to "pure" music, without any trace of any [folk] source, anecdotes, etc. For instance in Miraculous Mandarin, it's a ballet and he followed a story, but here he came back to his love for chamber music. Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta is a kind of expansion of chamber music. All through his music, also in the Concerto for Orchestra which comes later, you have this kind of "night music." The third movement is certainly in this direction: it was a kind of image or music inspiration which permanently permeates the slow movement, with tiny figures, short, and the type of sonority in the high registers of the instruments.

The most extraordinary movement was the first, this big chromatic fugue, which is really unique in his work. Even in the Quartets, you don't find that. The only example of work as chromatic as that, and as systematic also, because it's based on the cycle of fifths. It's like a fan, it opens and it closes; all the structure is very visible. The fourth movement and the second are much more Hungarian, with a kind of rhythmical vitality, especially the fourth one, with a kind of folksy tune.

Béla Bartók, "Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta Sz. 106 - 3. Adagio"

V. Anton Webern, Six Pieces for Orchestra

He was a very important figure, and completely unknown in 1945. Who knew Webern? Maybe in Austria, those who lived before the Anschluss, before Hitler came, but it was very confidential at this time. You can apply to Webern what [Charles] Sainte-Beuve in France said of Baudelaire: "The Kamchatka of poetry." Webern was a kind of "Kamchatka of music," an unknown country of music. That's true; for me and people of my generation, he was a radical—you couldn't be more radical than he was. Therefore he was a striking example. After the Second World War, there was a kind oftabula rasa, 'We must begin again from scratch.' And he was the model to begin from scratch. We admired him a lot, and we copied him a lot.

I suppose he would've been astonished at the influence he had on younger people. You can understand, with the gestures of Stravinsky and Rite of Spring, how it was striking the imagination – it was very forceful. But the music of Webern in general, is tiny, very refined. The dynamic range is very small, generally; in these pieces, out of six, there is only one, which is a kind of funeral march, with a very big climax at the end. On the contrary, his music is very soft, delicate. The later works are still more discrete, and extremely short. His vocabulary was extremely condensed; I think of haiku in Japanese culture, where you have the whole world expressed in a few lines. As Arnold Schönberg says of Webern, 'He expresses in one sentence what people need a whole novel to express.' I think that's still true; to have a condensation of language and expression as strong as that, it is unique in the literature.

Anton Webern, "Six Pieces For Orchestra, Op.6 - #6"

VI. Luciano Berio, Sinfonia

It was commissioned by the NY Philharmonic, in the time of Bernstein. I think Luciano Berio was very impressed by a Mahler performance of Bernstein's and therefore, you find in the middle of Sinfonia…something he does not like to call a collage, but it is a kind of collage. There's Fischpredigt of Mahler ["St. Anthony's Sermon to the Fishes," from Mahler's Des Knaben Wunderhorn] performed, and he inserts excerpts of all kinds of quotes—[Hector] Berlioz, Beethoven, up to Stockhausen and myself as a matter of fact. It's a very extraordinary piece because, like Berlioz, Berio has a very strong theatrical imagination with his concert works. The theater pervades practically all of his work. Therefore, the Sinfonia is a real theatrical piece.

But we must not concentrate only on the third movement which is the most spectacular. [Regarding the second movement] he began to write a very short work for a chamber group on the death of Martin Luther King. He used a group called the Swingle Singers, who were very popular, and Berio liked the theatricality of this group. He used them not only singing, but also speaking quite a lot. When you are performing this piece on stage, you have to have the singers with a mic, because otherwise they won't be heard. And with the microphones they can sing, they can whisper, they can use different dynamic levels. They detach from the orchestra, and at the same time be completely coherent with the orchestra.

That's a work which I like, and which I could never have written myself. That's very attractive to me, because some works you say, "Well I am in this direction," but this one—especially the third movement—I could never have written it, and therefore it has a fascination for me. It's not just the use of another composer as source material; it is the complete background of the music. I admire a composer who can do that, and also keep his personality.

Luciano Berio, "Sinfonia, 3rd movement"

VII. Karlheinz Stockhausen, Gruppen

He is my generation, three years difference. Gruppen is one of the most impressive works he's ever written, for many reasons. First, it's for three orchestras in space: three groups, one in front of the audience, one of the left side, and one on the right side of the audience. I remember I gave the first performance, Stockhausen was conducting the left orchestra, I was conducting the right orchestra, and Bruno Moderna was conducting the orchestra number 2 which is facing the audience. I asked myself, with the very little experience I had conducting in 1958, how I could really get the piece performed correctly. Stockhausen had no experience at all. The only one of the three of us was Moderna who was an experienced conductor.

We were trying to cope with the situation; because with Gruppen you cannot just rehearse with the three orchestras together, you have to prepare the three separately, and then the conductors have to rehearse for themselves. The conception of time, for instance, is that one will beat in four, the other will beat five, etc. It's constantly shifting. There is one who must give the main tempo, and the other two must be dominated by this one and coincide. The funniest rehearsals are always between the three conductors: they're silent rehearsals, you see only the beat; you don't hear any music. Then to go back in front of an orchestra is suddenly something easier to do.

He was very keen on having a conception of multiple time [signatures]; the use of space was a consequence of that, or perhaps an incentive, because you can't mix tempi if you're all in a single group. Space was a way of making clear the polyphony of tempi. From time to time, he used it [the space] massively – for instance with a chord that goes from one orchestra to another one, which travels, so to speak.

Karlheinz Stockhausen, "Gruppen excerpt"

VIII. Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 6

I think it's one of the most difficult to conduct, not so much the first movement as the last one, because it's climax after climax, and if you do too much to the first climax there's no way of doing the other ones! Maybe I like the Adagio of the 9th more than the Adagio of the 6th, but on the whole, the 6thSymphony is always very impressive. Especially when I put them in relationship with the Three Pieces, Op. 6 by Berg. For me, the two works are very deeply related. As a matter of fact, I planned to do this program with the Vienna Philharmonic; I said 'Can we do the Berg Op. 6, the Webern Op. 6—which are very influenced by Mahler, especially with the cowbells etc—and the Mahler Symphony No. 6?' The representative of the orchestra said to me, 'Well, I think the brass would be dead after this program.' But you cannot resist, even at my age.

It was Symphony No. 6 by Mahler, as a matter of fact, that was the first Mahler symphony I did with The Vienna Philharmnic. So this recording is for me good memories.

Gustav Mahler, "Symphony No.6 In A Minor - 4. Finale (Allegro moderato)"

IX. Arnold Schönberg, Erwartung

There is very little debate [of his stature], but very few performances. I don't understand why conductors are not really performing these works constantly. You have these wonderful pieces that are conceived for the theater but you can play in concert also, like Erwartung, and Die glückliche Hand. And then you have an opera like Moses und Aron, which should be in the repertoire of all of our houses. It's a little more difficult than Parsifal but not that much. The works are composed in 1910 or 11, and 90 years later it shouldn't be a problem any more, but when people hear only the name of Schönberg they say, "Oh, I can't do it."

Our century is supposed to be the fastest, the quickest, the one which reacts instantly and likes progress —and sometimes in music, you find it's the slowest of all centuries. If you compare with Wagner, take Tristan und Isolde for instance, around 1860—90 years later, that's 1950, Wagner is no longer a problem. I don't want to criticize my century, but the process of absorbing what is composed during this century is a very slow process, much too slow for me.

Erwartung is a drama with only one person. It's difficult to put on stage, because first you have to find a personality which is exceptional. Because you never know if it's a dream or nightmare of a single woman or if there's something real. Her lover has been unfaithful and suddenly she discovers the lover killed in a forest. But you never know if it is in her imagination or reality. I have seen some productions which are not terribly convincing as to whether it's real or not. But musically, it's not a problem – it's as dramatic in places as [Wagner's operas] Tristan orGötterdämmerung, certainly.

But it's physically very demanding for a very short period of time, because the demonstration of the feelings is extreme, and therefore it's nerve-wracking, if you want to be involved completely with the expression of the music. I never separated intellect and feeling; the greatest composers have always married these two things. The composers who are just feeling or just abstract, are for me not composers, they are half-composers.

Arnold Schönberg, "Erwartung" (excerpt)

X. Pierre Boulez, Repons

The real translation is "responsorial." In the church, especially the church of long ago, you had a priest who would say a sentence, and the crowd would answer. And this piece is between a group of instruments, and solo instruments.

You have in the center of the hall, which is not a normal hall but could be any kind of space, you have some strings, brass, woodwind, which are acoustic. You have the audience around that, and behind the audience you have six soloists – two pianos, one harp, one cimbalom, one vibraphone and xylophone/glockenspiel. These six instruments are amplified, and for some passages, transformed by electronic devices. Some of the sounds are un-tempered; you don't have only the half-tone, but other types of intervals. Therefore the audience is taking in a whole atmosphere of sound,which is in front of them and behind them. The main group sound is not moving – it is in front of the audience. But the sound of the soloists is traveling, so you have a responsorial between the main instrument and the soloists.

It's difficult to put on a recording, but we have developed a program at IRCAM which can give the illusion of space. We took a long time with engineers at Deutsche Grammophon and IRCAM to organize a pseudo-space which can be convincing. It's like a photograph of a mobile by [Alexander] Calder; you can imagine what it is, but it's on a flat surface.

I have faith in these new tools. It is not a religious admiration in technology, but you cannot resist the expansion of the tools. The development of iron in the 19th century put the piano in quite a different perspective, when the tension of the strings was possible at a bigger scale, and the sound was on a bigger scale. So the piano changed from the beginning to the end of the century. Right now, we cannot resist the invasion of electronics, because they are there in life and why not in music? It's not inhuman, as it is generally said, because I don't know any instrument more inhuman than an organ, and there is great music for the organ. There is and there will be great uses for new ways of approaching music.

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿